Coming back from SREcon 19 Americas in Brooklyn (catch up with Tanya Reilly’s conf report) and Chaos Community Day 19 in Manhattan (Nora Jones’ Chaos Engineering Traps), Resilience Engineering has had my full attention lately. I’m thoroughly encouraged to see so many folks interested in it and speakers from many different companies contributing their shared experiences to a field that can benefit so much from more perspectives.

Resilience Engineering has by no means hit a saturation point in the software development industry. Not everyone has opportunity to attend related conferences, political capital to execute upon it, or simply they don’t agree with the philosophy. Changing us from old ways is hard. That said, I definitely get a sense from folks who want to see it put into explicit practices with a little more substance or searching for new ways to implement ideas that itch in the back of their minds. In short, people are asking a simple question about Resilience Engineering:

What’s next?

We like our shiny tools, new topics to delve into, and how we can make a bigger splash in the industry, so naturally “next” could fall into the trap of “different is good”. I’m taking up this challenge of prognostication not because I’ve exhausted the topic (definitely not) or that I believe I know for sure what lies around the bend. I do think it’s a useful mental exercise to consider what needs currently exist that aren’t being met and the trajectory for existing practices.

For once, I’m also excited for replies of “You forgot to include..”, “What about…” and everything under the sun I don’t mention, both from folks deep in Resilience Engineering and those who push back against some common RE beliefs. I’m hoping for a lot of “Yes, and..” responses. Even being wrong (maybe especially?) will produce a lot of great learning.

Three things in particular come to mind as I’ve thought through this. They’re large enough questions, ones without hard boundaries or concrete answers (at least, not yet), and hopefully should generate plenty of food for thought. Here’s what I’m hoping to see in the coming months and years ahead.

1) Making Resilience Engineering more accessible

Right now, if you speak to folks in the field, they’ll happily offer you a ton of blog posts to consume, conference talks to watch, twitter accounts to follow, not to mention enough books and pdfs to read for 3 lifetimes. That’s great and I love that our community so warmly encourages folks to join. It’s a lot to work with, though, and it can feel daunting. We have a few 101 packets floating around- the Chaos Engineering report from O’Reilly, Etsy’s Debriefing Facilitation Guide, or Pagerduty’s Incident Response docs. So there’s this wide gap of quick starter guides on one side and all the deep knowledge in the field on the other. How are we seeding companies to improve and not just companies large enough that have money/engineers to support teams dedicated to it? How are we setting up our newest engineers just getting into tech? How do we break the habits of established engineers who want to push back without “getting too academic” (which is a weird slap to academia).

This stuff is complex, but not necessarily difficult. Fortunately, managing complexity is a big part of Safety and Human Factors.

We need to work on more information that doesn’t require you to attend Lund University (though a fantastic program!) to start practicing the fundamentals. Does that mean another series of blog posts, more conference talks, engineer rotations between companies? Possibly, but that adds to the volume. What we need is a streamlined on boarding of sorts, concise and focused on what it means to learn.

And how are we directing folks who have the time/energy for this? Lorin Hochstein at Netflix has a treasure trove of papers in his Github repo, and while not exhaustive, it can still be dizzying to know where to start. Which are the papers or books that are good for dipping a toe in the water, and do we have a level of progression? Does your role in a company factor into which materials to move on to or that demand more attention? For us to really understand Resilience Engineering, we need to know how to teach it to others in a way that makes sense.

2) More than the Philosophy of “no”

Tanya‘s post on SREcon 19 Americas (linked above) is fantastic. Even if we don’t always see eye to eye, her points are worth considering. I think a lot of RE conference talks and discussions have a tendency to point out the wrongs we’re continually committing. I myself am not innocent here – see my thoughts on Root Cause, Error Budgets, and Incident Management.

There are lots of reasons behind this. For one, we are looking for provocative talks to shake things up a bit. Some of it can potentially be attributed to “there’s no such thing as bad press” to gain attention on a subject matter that warrants it. Some of it we’re earnestly trying to share and looking to push more on the perceived boundaries (how many talks lately have “No root cause!” as a talking point?). And some of it might be that Incident Management, Retrospectives, and Chaos Engineering are relatively well described in the tech zeitgeist (if imperfectly or evenly), so we’re looking to push the boundaries to stand out more.

That said, we have to be more in Resilience Engineering than the naysayers repeating “hey everyone, you’re doing it wrong”. I often hear people cite reasons for using RCA or Error Budgets as “Well, it’s better than nothing!”. I understand that. It’s scary to be lost without a guide even if a deeply flawed one. We need to come up with the paths forward on how to do it right as well – we can’t rely on saying “do a blameless post mortem!” and call it a day. What specific steps are required for building a program from the ground up? How are we being proactive – and how do we all get on the same page on that? I think it’s a push-and-pull to get good at this while avoiding Resilience Engineering falling into the traps of DevOps, Agile, and other practices that have been taken over by marketing. We have to avoid the pitfalls like templates in Retro’s but also have focus and direction to provide to people.

I can imagine many of my colleagues disagreeing with this viewpoint of Resilience Engineering. After all, we’re the “blameless post mortems” folks. We don’t want to point fingers! This is a fine sentiment and I agree, there’s a lot of proactivity in our studies we push. But when we chip away at self-described industry standards (avoiding the term “best practices” intentionally here), we’re going to kick up some dust. In doing so, there’s a reputation being built. Fortunately, there’s a great solution – promote all the positive aspects of our work! Let’s start coordinating more on shared models, share our experiments with what’s working and importantly what’s not.

3) Cultivating Expertise

This is the hardest of all. This is nebulous, perennial, and a moving target. How do we prepare for the unknown to make resilience a thing? As soon as we know it, it’s no longer in the unknown!

Incident Management, Retrospectives, and Chaos Engineering are three amazing places to do this. I bet there are more strategies than “blow it up in a small way before a larger failure, learn during the explosion, and discuss the fallout afterwards”. The concept with regard to Safety-II of learning when things goes right is enormous in scope. What about the infinite things we’re constantly doing, judging, thinking about, and sharing should we explore further? When we say “be wary of templates” – ok, but what then? I need to start somewhere!

I’ve mentioned to several folks interested in resilience engineering and tech that I’d love to see more works around this. You’re in a retrospective, you’re trying to be blameless, you’ve got timelines laid out…but how are we making engineers actually good at getting experts to share what they don’t even know they need to, and what language do I use when tempers rise? How do we get really good at building intuition? It’s like asking “how do I prepare for everything that could be asked in a hiring interview?”, something you could spend forever diving into and never hit bottom. And for all of this, how do we know we’re getting good, that we’re actually on the right path? Especially since so much of Resilience Engineering is a separation from “hard” metrics (don’t use MttR, don’t rely on Severity for incidents, etc.), this makes it all the more difficult to say “yes, we’ve progressed this far”.

Next steps

I’ve two particular ideas to seed here.

The first is not my own but I think someone could make a big splash here (hint hint). There’s a concept of the “messy details” (associated paper) in every day work where experts reflexively and seamlessly perform tasks that require handling many moving parts. If you’ve ever had to ssh into a production box and grep through logs just to confirm suspicions about your code in a live environment, you may have a sense of this. Perhaps you’ve seen a senior engineer who “just knows” where problems are in their day to day, solving them before anyone is the wiser. There are of course better ways to go about sussing out this kind of information – but what is it about the expert’s understanding of the system that both allows them to do this and demands they work in this capacity? I’d love to see a practice with tangible steps that can highlight how we might look at this in a consistent and meaningful way beyond something as impossibly comprehensive as, say, a running log of every engineer’s actions.

The second is something we’ve said about all manner of things in software engineering: we need to improve representation. Getting folks who can come at this from different angles, have wide ranging backgrounds, and can speak to different problem sets will be seriously eye opening. Who knows how many of our approaches or standards are assumed, that need to be challenged, or are insufficient for a wider range of needs because so many of us tend to fit into stereotypical engineer types. Maybe all of the under represented folks in tech who are just starting to get the tiniest bit of the door opened for them could benefit greatly from this work – and how much of their experience could in turn bolster our field! Let’s start focusing on what we can explicitly do to foster diversity and inclusivity in Resilience Engineering.

Going about this both is bigger than a blog post, or a paper, or a book. I’m not fully equipped with everything that needs to be done. It’s not a quick turn around and will take a significant investment in time and energy. I will say that I’m highly confident it will pay off, so it’s in our best interest to begin now and I want to be available in any way I can to make it happen.

So, now that I’ve peered into my crystal ball – what am I missing? Hint: there’s a lot, so don’t be shy.

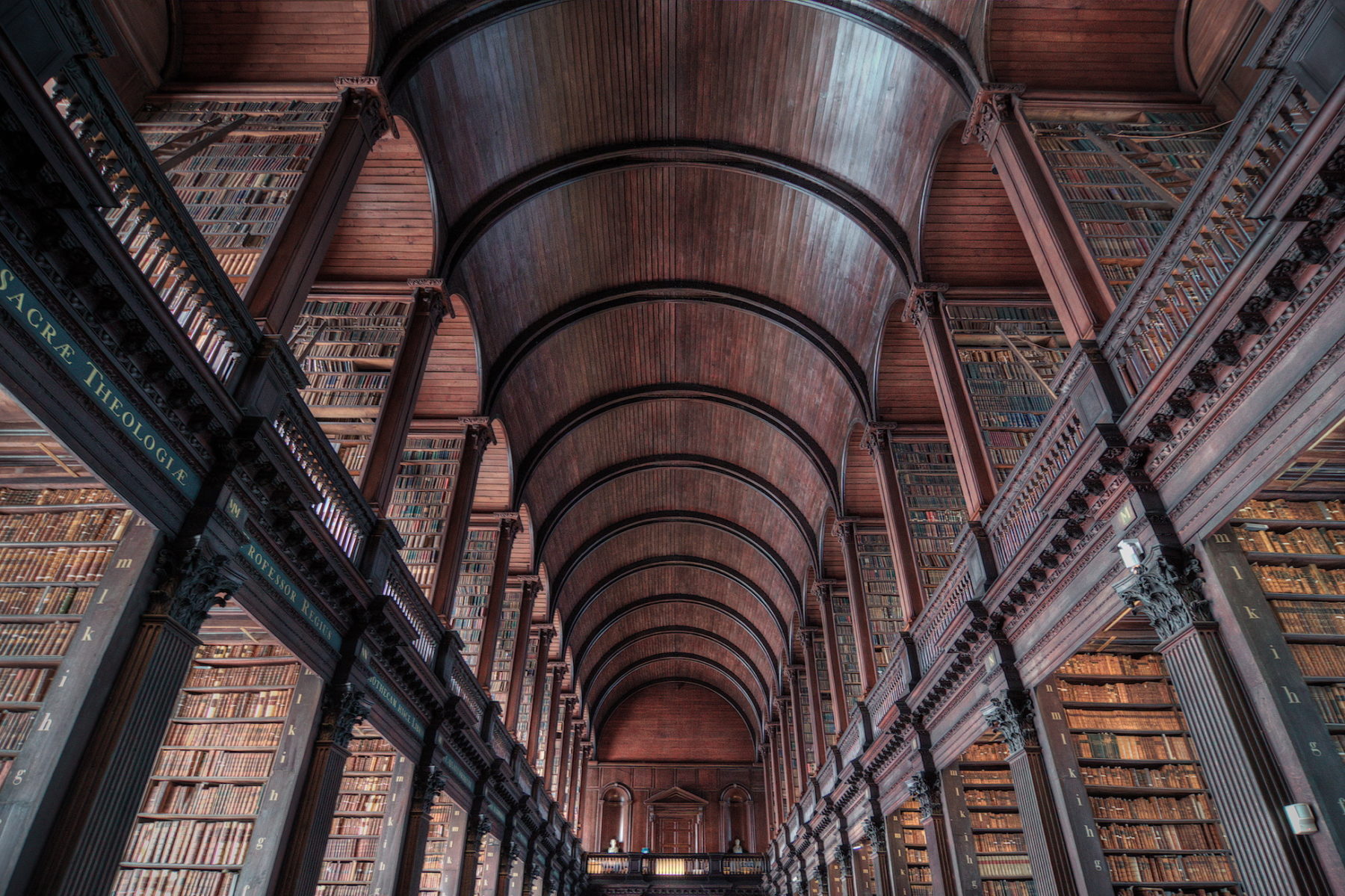

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/53264931@N03/27658701289

1 comment for “Peering into the future of Resilience Engineering in Tech”